The alpine guides Tomas and Silvestro Franchini brought their multipurpose technique on the Peruvian mountains of the Cordillera Blanca, opening a new route on the Nevado Churup.

The alpine guides Tomas and Silvestro Franchini brought their multipurpose technique on the Peruvian mountains of the Cordillera Blanca, opening a new route on the Nevado Churup.

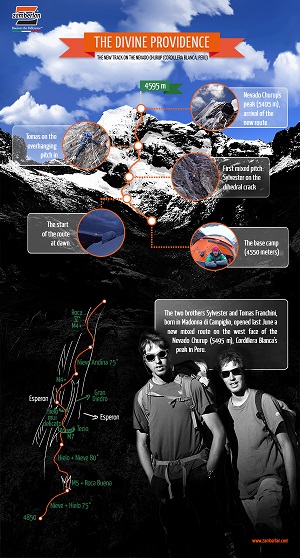

From 2011 to today they have opened more than two dozen new rock, ice and mixed routes, starting from the Brenta Dolomites to Patagonia. Tomas and Silvestro Franchini, born respectively in 1989 and 1987, spend most of the year as mountain guides and ski instructors and in activities like climbing walls. The two brothers of Madonna di Campiglio are among the most active Zamberlan ambassadors thanks to the mixed technique approach with which they face the ice and rock and walk at high altitude. In a recent expedition they climbed the most important mountains of the Cordillera Blanca in Peru. What follows is the interview derived from the accounts of their ascent to the Nevado Churup (5495 m) last June, with the opening up of a new mixed route , at 5480 m, promptly named “La Divina Providencia”, considering the climbing difficulty of M7.

1) Let’s start with the account of your climb to the Cordillera Blanca: how did it go?

Our initial plan was to climb the Cordillera Huayhuash which is a mountain range that has a very wild shape, ideal for those like us, who always want to explore the remotest mountains with still inviolated walls. After a period of acclimatization in which we climbed peaks between 5400 and 5800 m, the idea was to delve into the Cordillera without returning to civilization for at least 15-20 days, but during the trecking phase before the trip, walking through the village, I was unfortunately bitten by a dog. There are so many strays that roam the city and the hygiene is not the best, so I have been advised to do the rabies vaccine, associated with antibiotics, with the obligation to present myself to the hospital every seven days for a booster. Certainly not the ideal situation to test the type of enterprise we had in mind, so we decided to visit the Cordillera Blanca, which is a bit ‘more accessible from the city of Huaraz’ basis: each week we went exploring a different valley, always trying to be in the hospital at seven in the morning and to leave immediately after. Despite setbacks, we are happy with what we were able to do and we are proud we have brought our rather complete mountaineering style in these distant peaks, having made high altitude climbs, mixed and ice climbs and sheer rock climbs. We have opened a beautiful mixed route on the Nevado Churup considering a difficulty of up to M7 which is not so common for the Cordillera Blanca. Later we moved to the Quebrada Paron where we climbed the big walls of the Esfinge (5330 m) which is famous all over the world; there we probably made the first repeat of “Los Checos Bandidos”, which is also one of the most challenging rock climbing routes in the area, having difficulties up to 7c. Considering the incredible potential offered by the place, the desire to climb on the rock was great. Being in an environment where the high altitude predominates over everything else, we decided to try the Nevado Chopichalqui of 6354 m. It represented a good occasion for us, since we do not have a high-rise land at home. The risk of slab avalanches on the last slope before the final ridge stopped our attempt at an altitude of 6000 m. In the final week we decided to give it a try: we attempted the highest and most feared Peruvian mountain, the Nevado Huascaran Sur (6738 m) with an innovative and fast way. It is a rather unconventional strategy, dictated by the choice to skip various fields, to make a windy bivouac at 6000m in order to conclude the climb in just three days.

2) What does it take to become polyvalent climbers as far as the difficulty of combining different techniques and approaches is concerned? I’m thinking about a different physical preparation for example.

In part yes; in the end we made a rock climb of 7c, which is a quite high level. A climber climbing only on rock has a very specific body, but climbing a mixed route or on ice, especially in far environments with long stretches, requires a different body because the day to be addressed is longer and more tiring. The backpacks are bulky and the routes along the wall are long and tortuous. A climber who climbs at high levels on both rock and ice, is usually not so strong in walking, because he has a different body type. This is a sport which requires rather strength and technique than a specific body and physical effort.

The preparation is different in the sense that it is specific both for rocks and walks. Sylvester and I do not follow a precise method, we are used to do a bit of everything here on our mountains and soon we will be able to bring our style of ranges climb to the Cordillera. In Peru, we achieved to make ice, rock and walk at high altitude. We also climbed the Huascaran, the highest peak of Peru (over 6700 m), and we did it in two days. The third day we climbed down hill while most of the climbers pass through the various base camps.

3) What does it mean to renounce to pause in a base camp during a climb (or descent) like this?

You have to be faster, it’s really just a choice of strategy. If you need to rest in all base camps it means you have heavier backpacks, you’re slower and you do everything more calmly. We have chosen a light-weight style of climbing that allows us to be faster …also because we had just a small time left before returning to Italy and we were otherwise risking to remain in Peru [laughs].

In general though, we like to go fast. Sometimes we prefer to climb up or down at night rather than stopping to camp out on the wall. We think the lightness is also a safety issue: if one is more lightweight one can climb more safely. In a way it’s a bit ‘Alpine style’, to skip the camps and not to carry around all of the equipment.

However, we have experienced different styles of climbing. In 2013 I went on an expedition with Ermanno Salvaterra on the west wall of Torre Egger: we had to adopt a heavy-weight style that involved more days on the wall, with a very difficult and artificial climb. At that time I did it to try a new experience. I have always been intrigued by mountaineers who are able to remain several days on the wall and who climb with some sort of a capsule-style (both equipment and portaledge) on the wall. But the preferred style for me and my brother is the lightweight. It is an alpine style which is both fast & light.

4) Concerning tools and technical equipment, what did you use on the Cordillera?

I used a lot of semi-crampons-shoes, the Fitz-Roy Zamberlan, initially because they are very light and ideal for trekking stage. In the end, I made such a good experience with them that I used the same boots to climb the new route on Churup up to nearly 5500 m. I climbed Pisco during the acclimatization phase up to nearly 5800 m, and then I made the attempt on Chopicalqui up to nearly 6000 m. If we had faced the Cordillera Huayuash I would have used the Karka Boots, which are boots with a removable liner, suitable to stay more days on the wall and to camp out without risks from the cold. My brother Sylvester instead has mainly used the Eiger boots. They are some sort of an intermediate model between Fitz -Roy and Karka, a good compromise between precision and warmth. For the rest among the main equipment we had brought a very light, two-seat Ferrino tent, which we also used for a very windy camp at 6000 m, a special sleeping bag stuffed with feathers with a synthetic treatment against moisture, high protection glasses and of course gloves and specific ropes.

5) What does it mean to open a new route? Which are the main difficulties and how do you overcome them?

Undoubtedly the unknown represents the greatest risk, but it also makes the challenge more exciting.

To open a route is one of the best things in the world for us, because we love the exploration, the adventure, finding new places and new ways to climb up. You never know what you will find, apart from the fact that there is a blank wall and then a stretch of unspoiled nature. But the mountain is our home, our habitat and what we like to explore, so the meaning of fear is a bit ‘different for us.. let’s say the prevailing desire is to explore.

6) Now, as far as nature is concerned, I draw inspiration from the dog bite to ask if you have fully recovered from it and and if you have had other “special”meetings with the fauna of those mountains.

Yes, I have recovered completely, thanks. After the antibiotics cycle everything has gone back to normal. As for the fauna, I have no other particular encounter to tell you! There are beautiful birds of the family of condors that fly in pairs, then there is some species that has amazed me, a kind of crossbreeding between a hare, a marmot and a squirrel. It is a very fast animal! We also saw mountain cats with their very thick tails but in general, there is no way to have lots of interactions up there.

7) Concerning the Cordillera Blanca and the mountains of Peru: Are there specific differences compared to European mountains?

Compared to our Dolomites the Peruvian mountains are huge, they are really high and that’s the reason why those mountains are very dangerous.

Perhaps, a substantial difference between our mountains, the Alps, and the mountains of Peru is that you can climb ours in all seasons, all year long. In the winter it is more difficult, while in the summer it is easier, but it is doable in any case. In Peru, however the mountain conditions are very different from year to year, and in some cases it is too dangerous to climb them. It’s not even a question of climate, in fact in the dry season, with respect to Patagonia, it is generally very stable. It is the shape of the mountain that hides possible pitfalls … you can suddenly find an open crack that was not there the year before, a serac can come off and obstruct the path … The rock structure may in some case hold some bad surprise.

A good example of it is our attempt on the Nevado Chopichalqui (6354 m). Two groups before us had withdrawn because of some crevasses that had not been there the year before; Sylvester and I managed to bypass that spot, following a ridge, which was a little ‘exposed, but at 6000 meters we had to turn around because of a very dangerous slope that could bare dangerous avalanches: maybe it was a bit’ too soon, the snow had yet to settle and probably it hid the slabs. Even the Peruvians say the Cordillera can be very dangerous. In fact the locals demonstrate a great respect for it. To them it’s almost like a sacred mountain. I feel like they respect their mountains much more than we do with our own ones.

8) What about tourism and pollution?

In general, we expected the Cordillera Blanca to be much more popular, however we chose the places which are a little ‘wilder and we managed to avoid the bulk of people. Also the fact that this mountain range is so large, makes it easy not to meet so many people.

There is zero garbage on the mountains while in the city there is some, also because of poor hygiene conditions due to an extended poverty which does not yet embrace the philosophy not to pollute, but we have gone trough the same condition many years ago. It’s just a matter of time.

9) How was the weather like? Did it create any problems?

In Peru, when the sun is shining, temperatures are very high.As soon as the sun goes down there is an impressive temperature range that makes the temperatures fall three seconds after sun set.In general, however, the conditions are not extreme: at night we found temperatures around -10 / -15 degrees, during the day instead it was hot. Nevertheless over 6000m everything turns around: it is very cold even during the day.

10) Tomas and Sylvester, brothers of almost the same age: How do you experience this relationship which is at the same time familiar and professional, where you share a common passion for the mountains?

My brother and I have a very special relationship. We have always climbed the mountains together and we have always wanted to be independent as soon as possible. To be honest, we are very proud and that has led a few times, when we were still very young, to take some unnecessary risk. We learnt a lot from those experiences. Spending much time together, in an everyday life, does not mean to avoid confrontation. The mountain though makes us grow increasingly closer and gives us the necessary motivation to help each other. In the end, when there is a very difficult experience to undertake like this, we always search each other, because we know each other so well and we trust each other so much, that we forget about any possible bickering. Then we also have many other friends and climbing partners with whom we often climb, but the most beautiful things we have done them together.

11) What are your future projects, climbs, initiatives?

A project we have in mind for quite some time is India! It is not easy to find partners to share the expedition and expenses, but we hope to carry out the project India as soon as possible.

INFO: Zamberlan